Sleep and performance are closely interlinked; inadequate rest can reduce athletic performance while increasing injury and illness risks.

Athletes often struggle to get enough sleep due to training schedules, travel arrangements, and competing academic demands among younger athletes. Studies demonstrate that getting adequate rest improves reaction times and accuracy, while its impact on endurance, strength, and sprint is less clear.

Mood

Human sleep helps us process emotions, enabling people to overcome negative ones more effectively and maintain balance in their emotional states. A lack of sleep has been linked with mood disorders like depression and anxiety, which in turn have an adverse impact on performance; hence, it is crucial that good sleeping habits and regular sleeping patterns be prioritised so as to increase overall mood enhancement, which in turn increases performance.

An effective night of restful sleep is an invaluable way to ease a stressful day and prepare yourself for the new challenges ahead. Sleep helps us recognize our emotions and process them more fully, which may affect how we react to stressors in the future. Furthermore, sleep improves how our bodies process glucose and insulin, which in turn enhances our mood.

Sleep can be defined in a variety of ways; physiological definitions dominate when it comes to categorizing different stages, while behavioral and phenomenological approaches have increasingly gained popularity as complementary methods of understanding it. When used together with physiological definitions, they offer another perspective, helping to identify when these perspectives overlap or diverge in definitions of restfulness or sleepiness.

One reason behavioural and phenomenological definitions of sleep are effective is that they more closely match subjective reports of internal states like dreaming or unconsciousness, as well as changes in nervous system responsiveness (Destexhe et al. 2019).

Objective measures, such as the duration and quality of sleep, support these reports of internal state. Noninvasive neurophysiological techniques such as electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can collect measurements.

Study results on athletes showed that those getting less than seven hours of sleep per night had an increased risk of mood disorders like depression and anxiety, which negatively impacted training performance. When faced with stressful situations, they often overreacted; those who prioritized sleep by adhering to regular sleeping patterns were better equipped to deal with the pressures of competition.

Reaction Time

Career or athletic demands can put a significant strain on students and their families, leading them to cut back on sleep or exercise time and instead prioritize other healthy habits. But don’t despair—making up these deficits by prioritising sleep and other healthy practices is entirely possible!

Studies on the relationship between sleep and academic performance reveal that students who prioritise sleep are better equipped to meet the challenges associated with being active students. Studies have also indicated that the more hours slept per night, the better grades students receive; sleep helps strengthen memory consolidation. Athletes who prioritise restorative sleep also benefit from enhanced mental and physical performance due to adequate rest.

Athletes require ample rest in order to achieve peak performance and avoid injury. Studies have revealed that adequate rest benefits the nervous and endocrine systems, reduces immune-inflammatory reactions during training sessions, and enhances memory retention and learning for subsequent sessions.

But it can be challenging for athletes to ascertain if they are receiving sufficient sleep due to physiological criteria that can be hard to identify, including changes in neuronal activity that are indicative of restful slumber, such as decreased responsiveness or dreaming.

Consideration should also be given to how individual sleep criteria vary—even within an individual—with significant overlap among physiological, behavioral, and phenomenological definitions of restorative rest.

Sleepwalking or falling asleep at home could still meet the physiological criteria of being in REM sleep because these processes are universal across mammals and involve similar EEG features. Therefore, when assessing an athlete’s sleep, it is crucial to remember that the physiological definition of sleep should serve as the criterion for determining an acceptable episode of restful slumber.

Focus

Sleep is defined by decreased brain waves associated with awareness of external stimuli; this distinguishes it from states such as coma, hibernation, or death. Sleep is essential to survival and appears to serve multiple vital purposes.

Sleep may help regulate emotions and strengthen one’s ability to understand other people’s emotional expressions. According to several studies, those who sleep more tend to possess higher levels of emotional intelligence. 1

Sleep can also play an integral part in learning and memory consolidation. According to researchers, sleeping reinforces certain synaptic connections that were active during wakefulness while weakening others; this process is known as neuroplasticity. 1.1

Sleep’s role in maintaining circadian rhythm and sleep-wake homeostasis may explain this trend, specifically through its ability to regulate an organism’s internal clock and cycles of sleepiness. The suprachiasmatic nucleus helps do just this.

Sleep can aid a person’s ability to think clearly and concentrate during the day. A good night’s rest allows the brain to recharge itself, so you can return to work or school feeling rejuvenated and alert.

Studies have also demonstrated that getting adequate rest can reduce students’ susceptibility to stress. This phenomenon is believed to occur because of the positive feedback loop that results when students prioritize sleep; those who sleep efficiently feel less stress during the day, which in turn improves their nighttime restfulness.

Although numerous studies have investigated the relationship between sleep and academic performance, most have relied on subjective measures of duration and quality. By contrast, this study tracked university student sleep objectively using Fitbit, a wearable device that tracks heart rate and movement patterns to measure how long someone spends in each phase of sleep, along with academic assessments completed over an entire semester to provide a more thorough analysis of its effect on academic performance than similar methods employed by previous research studies.

Endurance

Sleep’s primary goal is to restore energy systems within the body. Sleep also supports muscle development, increases bone density, and suppresses cortisol (a stress hormone that causes lethargy). All these benefits allow athletes to perform at their maximum potential.

Studies on various athletes demonstrate the importance of adequate rest for peak performance. According to one study, college basketball players who received nine to 10 hours of sleep had improved free throw and 3-point accuracy, as well as faster reaction times off of the start block, whereas another study demonstrated well-rested baseball players having superior strike zone judgement.

Sleep can improve glucose metabolism, provide energy, and reduce the risk of overtraining and injury. Sleep also helps the immune system. To achieve optimal restful slumber, create a regular sleeping and waking schedule.

Many people struggle to get enough rest, which is especially problematic for athletes looking to train hard and recover properly. Athletes need an environment free from distraction that allows them to rest properly so they can concentrate solely on training.

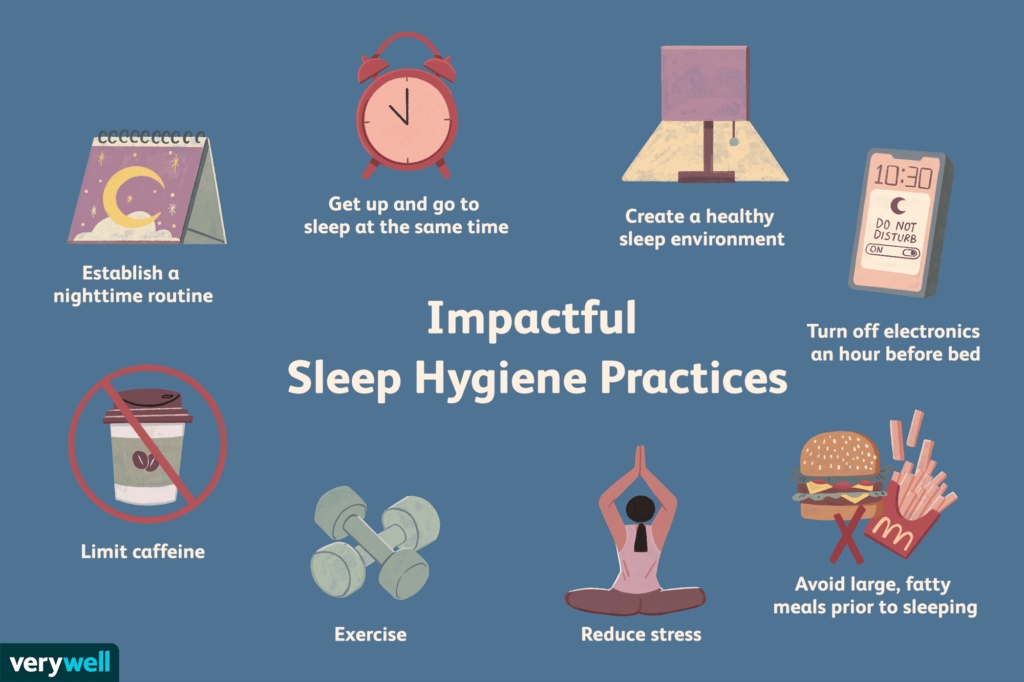

To achieve optimal sleep, athletes must form healthy sleep habits, which include adhering to a consistent bedtime and wake time, exercising before heading off to bed, limiting caffeine and stimulants in the afternoon and evening, and limiting naps during the day, which could interfere with quality restful rest that night.

Scientists and biologists often struggle with understanding what constitutes “sleep.” Sleep has an immense ubiquity across the animal kingdom yet has numerous implementations. Due to this diversity, a universal definition of sleep has yet to be determined. Most definitions do agree on some aspects; for instance, most animals spend most of their time sleeping during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, characterised by horizontal posture and relaxation of skeletal muscles. At this stage of NREM sleep, the brain is generally inactive, although some activity, such as sleepwalking or dreaming, may occur.